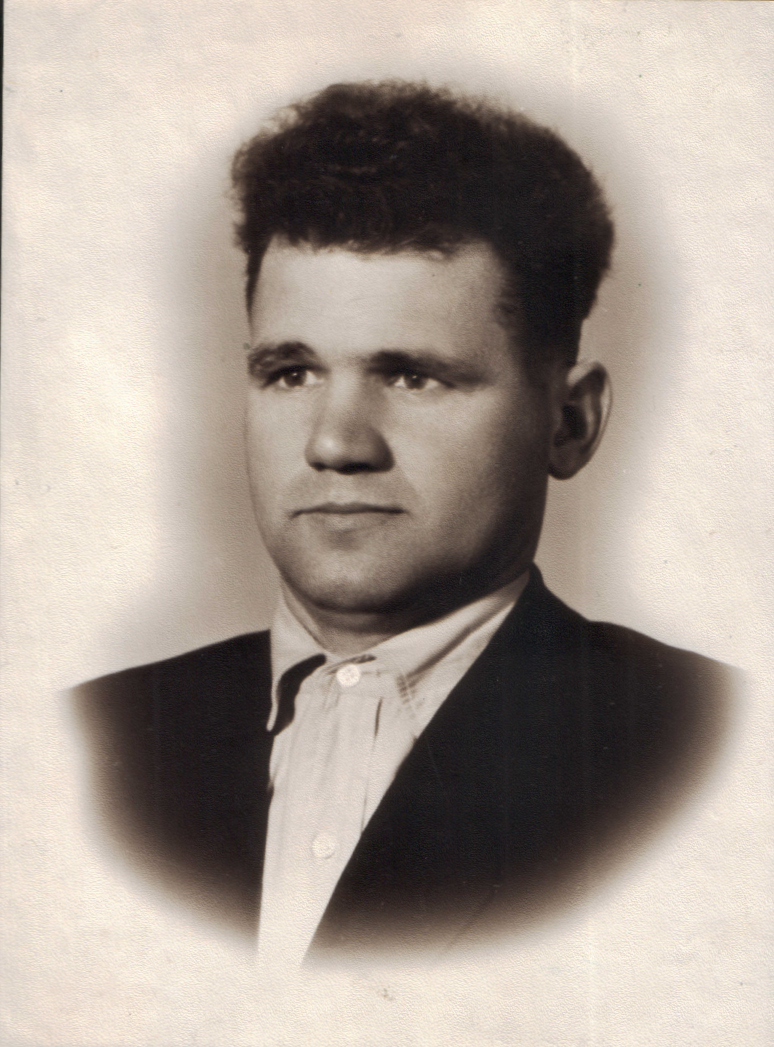

Andrei Iwanowitsch Moiseenko was born in 1926, day and month are unknown. After the Second World War, when he was drafted into the Soviet army, the date was set to 1 May. Since then his official date of birth is 1 May, 1926.

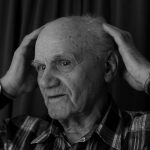

Andrei Iwanowitsch is one of the last survivors of the Buchenwald concentration camp.

This year he celebrated his 93st birthday.

Andrei was born in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which in 1919 had emerged from the People’s Republic of Ukraine. In 1922 it became a part of the Soviet Union, while the West Ukrainian People’s Republic was ceded to Poland by the Treaty of Riga in 1921.

Andrei was born in the small village Budionovka in the Chernihiv Oblast, about 150 km north of Kiev close to the present Belarusian border. He was the eldest of four children, the family lived in humble conditions. Andrei’s parents earned their living in the local kolkhoz (collective farm). Together with the children they lived in a wooden house in the village. When Andrei was six years old, his mother died of typhus. From this moment the father was alone with the four children. In order to nourish the family the father was forced to work ever harder, thus Andrei learned to take responsible for himself and his younger siblings at a very early age. One year later the father married again and two half brothers were born. 1941, with the second wave of military mobilisation, the father was drafted into the army. He died at the front. Andrei was at that point 15 years old and had just completed the seventh grade of the village school. His stepmother remained the only adult caregiver for the children. Rapidly approaching, the Front put an end to the hard but settled village life. During one of the severe German attacks the stepmother intended to hide the children in the basement. She herself left the hideout to warn the neighbours. Halfway to the neighbour’s house, she was fatally injured by German machine-gun fire. She died on the spot. After the sudden death of their stepmother, the children were suddenly on their own. Soon after, the entire area around Chernihiv came under German occupation. As he was the eldest of the children, Andrei was now responsible for the survival of his siblings. He had to undertake dangerous forays in the area around the village, begging local peasants for food. One day he was captured and interrogated by military police. They took advantage of his plight and promised him work to nourish his siblings if he’d go with them. Instead of the expected help, he was taken with others to the nearest railroad station, jammed into wagons and carted off, with unknown destination. After days of arduous train ride they reached Leipzig, the final destination. In Leipzig they all were brought to a place where local farmers gathered, and, like on a livestock market, chose the healthiest and fittest chaps for forced labour on their farms. Those who remained, amongst them Andrei, were put into a transit camp. The camp adjoined the company Hasag (Hugo Schneider AG), all inmates of the camp were used there as forced labourers.

The Hasag company had been the official armaments factory of the Wehrmacht since 1934, mainly producing ammunition. 1944, the Minister of Armaments and War Production, Albert Speer, granted Hasag the exclusive privilege to produce Panzerfausts – a single-shot anti-tank weapon. The factory was the sole manufacturer of this weapon in Germany and was able to continuously expand its capacities. Here began Andrei’s two-year forced labour. Initially he was assigned to the production and oiled machine parts, later he got an opportunity to slightly escape the focus of the watchmen and to work in the spare parts depot. Here he managed to come to terms to some degree. The fact that he had learned some German in the meantime appeared to be useful now. He befriended one of the older German workers who slipped him some bread and lard from time to time. However, the quiet was deceptive. Soon Andrei was suspected of being the leader of a group of young insurgents. In the factory repeated interrogations took place, especially younger forced labourers were affected. Andrei understood very early how the interrogation machine operated. Fictitious allegations, false translations, and the tricks of the Gestapo – the secret police. Group inquisitions were followed by separate interrogations. One of these interrogations still sticks in Andrei’s mind. As he sits with a Gestapo man at a table in the interrogation room, another standing behind him at the door, as the former stands up, taking a few steps towards the window, leaving his pistol on the table just in front of Andrei, as Andrei suppresses his urge to seize the weapon realising the ambush.

After this event, Andrei was put in a Gestapo prison in Leipzig. During the day he was taken to work on farms, in the evening he was brought back to jail. About two months passed, and Andrei still didn’t know why he had ended up in prison and what would happen to him after all. Eventually, he was moved to a prison in the city of Halle where he remained only a few days. From there he was deported to a concentration camp. Without any accusations or statements brought up against him.

He got into the hell of Buchenwald. He would be kept in this stranglehold for one year,

from May 1944 to April 1945. Andrei Ivanovich turned into prisoner number 19,852.

Alexander Bytschok and Andrei Iwanowitsch

70. anniversary of the liberation

Buchenwald, April 2015

Press Photo: Chicago Tribune

The number 19,852 had originally been given to another prisoner who was also from Ukraine, from the Poltava Oblast. It was passed to Andrei after the Ukrainian prisoner had been killed. In May 1944, the consecutive numbers had already exceeded 77,000. After his arrival, Andrei was immediately sent to the small camp in Buchenwald, in a barrack for around 1,000 people where a bed was shared by more than 10 prisoners. Death was omnipresent here, with the smoking chimneys of the crematorium constantly in sight. Until autumn 1944, Andrei had to work in the quarry. The quarry was one of the most dreaded places of work, it was situated about 1 km from the main camp. Here many prisoners became victims of the unbridled terror of the SS. In autumn 1944 Andrei was sent to the satellite camp Wansleben. Over 2,000 prisoners worked here in underground hangars in the production of grenade detonators, aircraft engines and parts of the V1 and V2 rockets. Andrei worked in Wansleben until the liberation of the camp.

As US troops were advancing on April 12 1945, the SS evacuated the camp and sent the prisoners on a death march towards the city of Dessau. After two days of march and many deaths, approximately one and a half kilometres from the execution site selected by the SS, the prisoners were finally liberated by the 3rd US army. It was April 14, 1945. The Buchenwald concentration camp had already been liberated on 11 April by the 3rd US Army. After liberation, Andrei and several hundred other survivors of the camp Wansleben followed the Americans on foot to a nearby town. Ever since the Yalta Conference in February 1945, it was clear that after a surrender of Germany, Thuringia should belong to the Soviet occupation zone. After correspondence between Truman and Stalin on 2nd and 3rd July 1945, the Soviet Army took over from the Americans and was instated as new occupation force. The Americans, knowing about the risks related to this, recommended the former prisoners to make their way towards the western part the country. Many followed this advice. Those remaining were handed over to the Soviet power, amongst them Andrei Iwanowitsch. They had to undergo rigorous interrogations again. During this, Andrei was declared to be of full age and was immediately drafted into the Red Army. 05.05.1945 was recorded as the official date of joining the army. In turn, many other survivors were denounced as collaborators and detained in the repurposed former concentration camps in the occupied zone or deported to Siberia instantly.

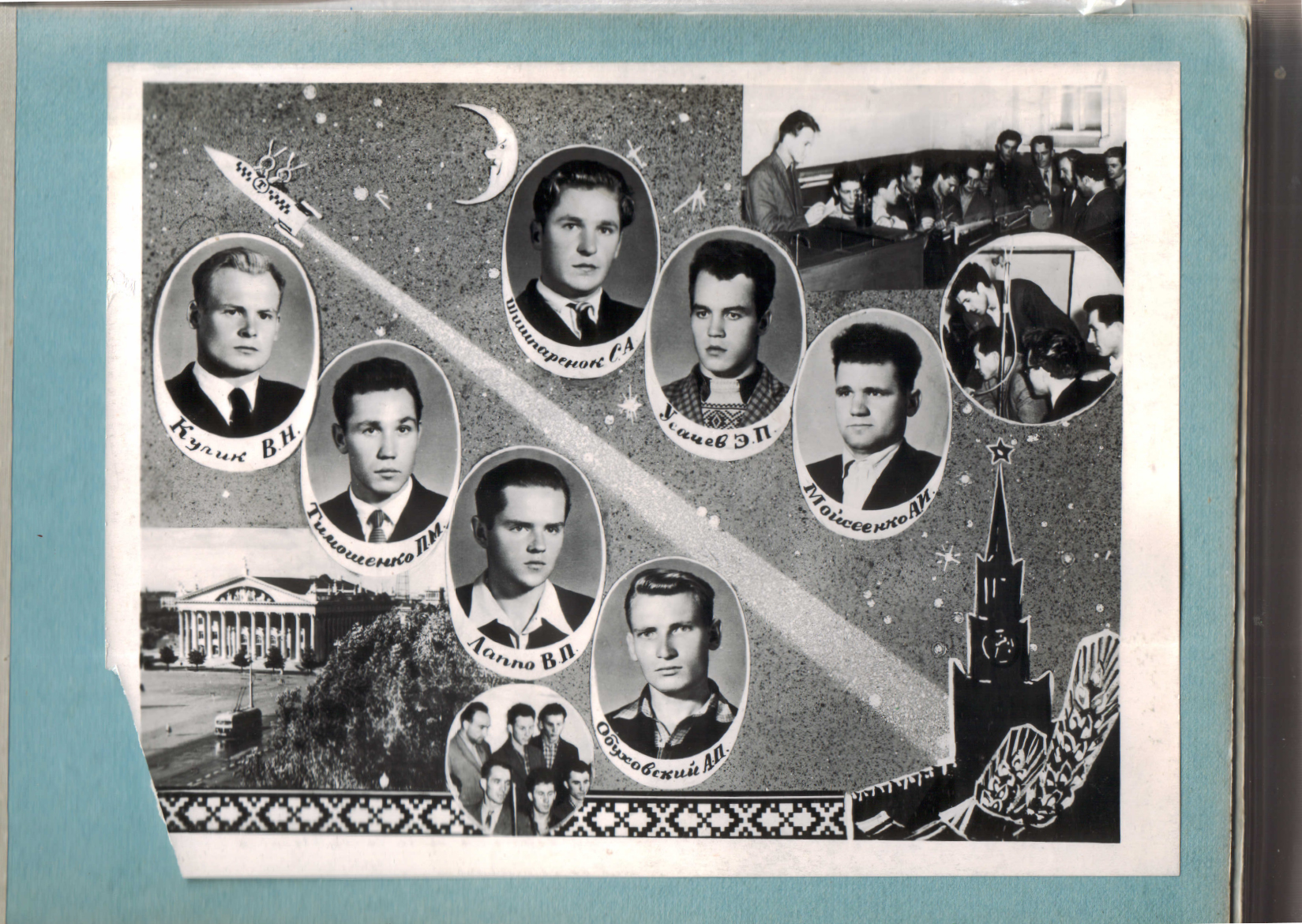

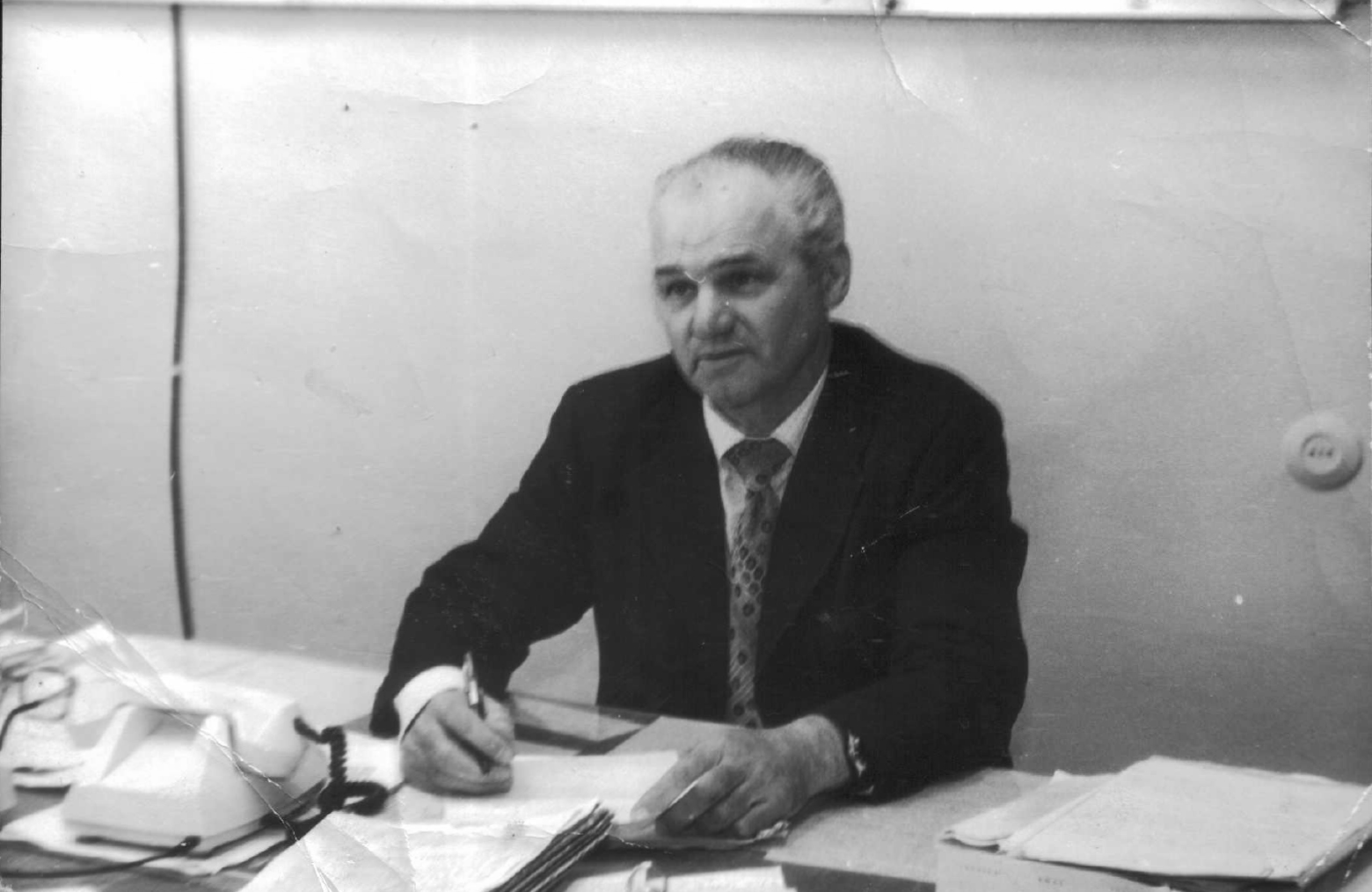

Andrei, however, was assigned to a garrison in the town of Babruysk in the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic, in today’s Belarus. In summer 1945, he and a troop of other soldiers headed on a 1.400km long walk to get there. In Babruysk he served as a military driver until 1947. In summer 1947 divisions were reorganised, and Andrei Iwanowitsch was sent to the 120th Guard Unit in Minsk. There he served until November 1950. After retiring from the army, he was granted permission to choose his place of residence. As he had no family anymore, he decided to stay in Minsk and started looking for a job. The first years he worked in a big building combine, in parallel he finished school and started with evening courses. He graduated from University in 1960 and got a job as draftsman in the design office of a machine manufacturer. He worked there for 38 years until his retirement, he left the company as department head in the design office.

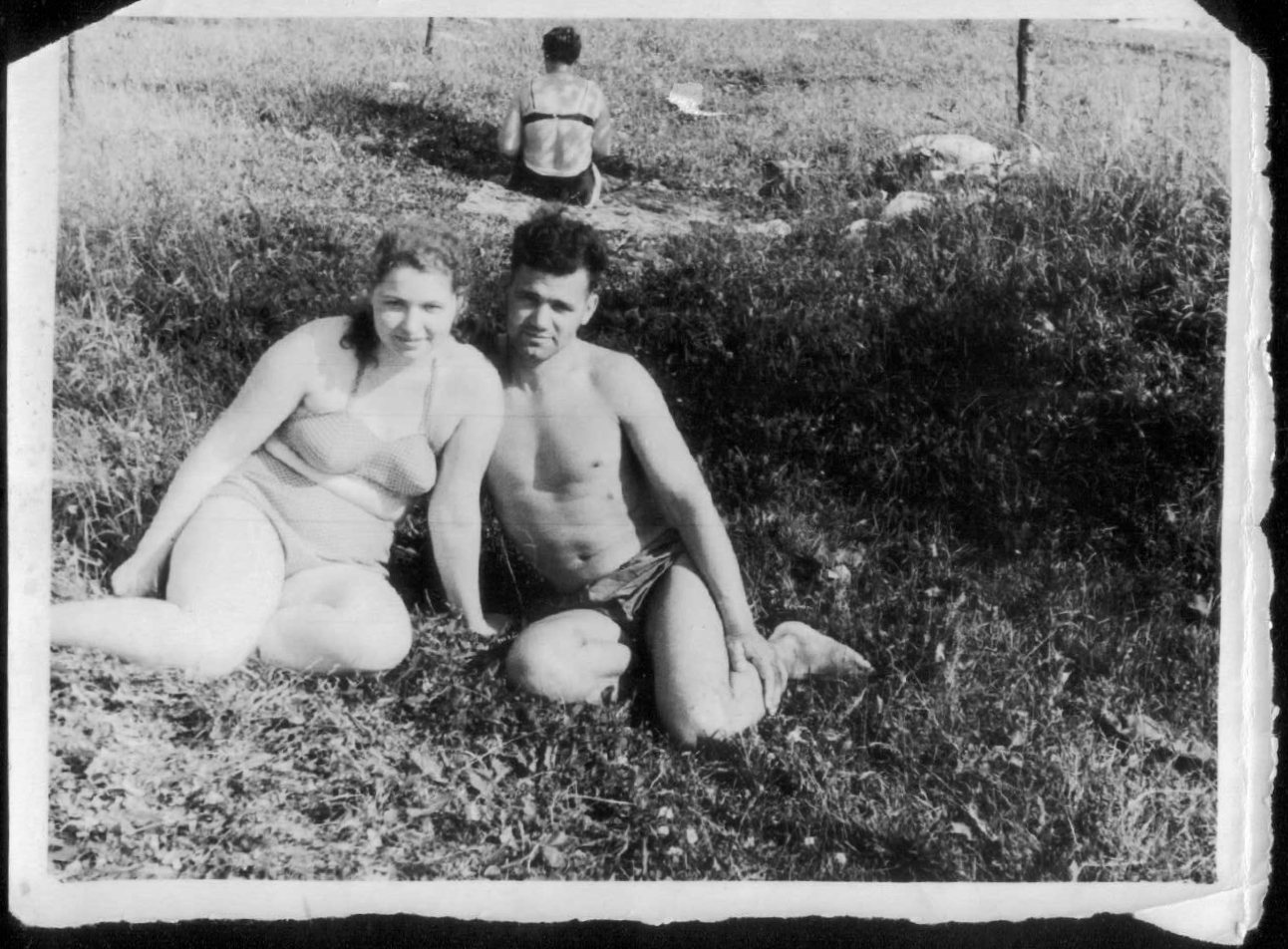

In summer 1952 Andrei met the great love of his life. After three months he married her. They had two sons. In the 1980s his wife died tragically, shortly after Andrei also lost one of his sons. To this day Andrei Iwanowitsch lives in Minsk.